Smart LLM Prompting in Healthcare—and Beyond

How many times have you heard about LLM prompting? How many times have you actually gotten what you need? You might have tried prompts like “summarize this discharge note” or “draft a patient letter,” but how do you know which prompt will generate real value? The difference between “nice demo” and “real value” often comes down to one quiet skill: how you prompt.

We have been systematically testing prompting techniques in real healthcare scenarios: EHR upgrades, hospital IT performance, clinical coding support, and analytics tasks done by clinical analysts and project managers rather than developers.

This article is a practical guide based on this internal work that you can use with any major LLM – whether you’re a CIO, product owner, analyst, or clinician working with AI-powered tools.

1. Why prompting matters for healthcare teams (not just developers)

Most developers interact with LLMs via APIs and IDEs; they build pipelines, not chat histories. But many healthcare decisions around AI are made before anything is coded— in a chat window, by:

- Business/system analysts

- Product & project managers

- Clinical subject-matter experts

The classical questions are:

- “What are our top EHR performance bottlenecks?”

- “How should we map these referrals into ICD-10 codes?”

- “What’s the best strategy to improve clinician satisfaction with the new system?”

In this case, prompting is the interface; be less generic and get a targeted assistant for healthcare IT, operations, and clinical workflows.

2. The anatomy of a good healthcare prompt

In our internal Clinovera sessions, we use a simple color-coded model for any prompt, regardless of the domain:

- Instruction – What do you want the LLM to do (summarize, compare, generate options, etc.)

- Context – For whom or what are you producing the content (hospital CIO, EHR migration, specialty, country, etc.)

- Input data – Logs, notes, transcripts, requirements, tables

- Output indicator – Format, length, structure, constraints

Example (EHR performance):

- Instruction: “Summarize the key system performance issues and propose improvements.”

- Context: “You are an IT consultant preparing a report for a hospital CIO after an EHR upgrade.”

- Input data: System logs (4.5s average response time, 12% failed API calls) + user feedback (physicians & nurses complaining about delays).

- Output indicator: “Top 3 issues + 3 recommendations, ≤200 words, professional business tone.”

Contrast that with a “natural” but messy prompt:

“Please just write something about hospital IT problems… short but detailed… not too technical but also professional… don’t talk too much about costs, but don’t forget them… propose improvements but not impossible ones… try not to be boring…”

It sounds human, but for a model, it’s full of contradictions, vague goals, no clear format.

3. Command-style prompts & style “augmenters.”

Most modern LLMs quietly understand “meta commands” at the start of a message:

- /summarize → condense into key points

- /list → steps, options, or items

- /format → output as table / JSON / bullets

- /rewrite → new tone/style

- /translate → translate into a target language

Plus “style tags” that aren’t real commands but work surprisingly well as tone controls:

- /CutTheBS → blunt, concise answers (great when the model gets verbose)

- /ProfessorMode → more academic explanation

- /TweetSize → ultra-short summaries

For example:

/summarize /CutTheBS You are an IT consultant for a mid-sized hospital. Read the EHR performance data below and list the top 3 issues + 3 actions in under 150 words, bullet points only.

This small layer of structure often makes more difference than switching models.

4. Core prompting techniques, with healthcare examples

4.1 Zero-shot—the “default” mode

What it is: You give only an instruction (no context) and rely on the model’s training.

Use it for simple, well-known tasks:

- Translating discharge instructions (“The patient needs to return in two weeks” → German).

- Short summaries of outpatient notes

- Basic classification (“appointment type: follow-up vs first visit”).

Zero-shot is ideal as your first attempt. If the answer isn’t good enough, you “upgrade” to more advanced techniques.

4.2 Chain-of-Thought—“think step by step.”

What it is: You explicitly ask the model to reason step-by-step before answering. Great for complex logic and multi-step decisions.

In our EHR performance example, the instruction becomes:

“Let’s think step by step. Identify issues first, then propose solutions. Show reasoning before giving the final summary.”

Now the model:

- List performance, reliability, and usability issues.

- Explains why 4.5s response time and 12% API failures are problematic in a clinical context.

- Proposes targeted fixes.

This is especially helpful when explaining system behaviors to non-technical stakeholders (CIOs, CMIOs, department heads).

4.3 Prompt chaining—one step, one goal

Instead of one huge prompt that tries to: analyze logs + collect issues + design options + score trade-offs + write a final report, we split it into a pipeline of small prompts:

- Gather info: Extract all performance-related issues from logs and feedback.

- List options: For each issue, generate 3–5 improvement strategies.

- Analyze: For each strategy, rate benefit, risk, and effort (low/medium/high).

- Recommend: Build an executive summary for the CIO.

Each output becomes the next input.

For healthcare, this pattern works extremely well for:

- EHR or LIS upgrades – logs → issues → strategies → roadmap

- Patient engagement – problems → engagement ideas → risk/impact analysis

- Workflow redesign – pain points → process options → impact vs effort matrix

Prompt chaining trades a bit of extra time for much higher clarity and traceability.

4.4 XML / JSON handoffs—make AI outputs machine-readable

When the output will feed another system (Excel, BI tool, internal app), we ask the model to produce structured data, not prose. We use simple XML templates like:

Or for options and analysis:

<result>

<issues>

<issue category="performance"></issue>

<issue category="reliability"></issue>

<issue category="usability"></issue>

</issues>

</result>

<result>

<analysis>

<item id="">

<benefit></benefit>

<risk></risk>

<effort>low|medium|high</effort>

</item>

</analysis>

</result>

In healthcare IT, that might become:

- `<issue category="performance">Average response time 4.5s vs 2s target, causing delays in record opening.</issue>`

- `<issue category="usability">Clinicians report frustration with slow lab result retrieval.</issue>`

Why it matters:

– Easy to parse and visualize (e.g., dashboards).

– Forces clarity – every issue must have a category and ID.

– Reduces “hallucinatory” extra text.

5. RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation)—and when you don’t need it

What it is:

The model uses a retriever to pull external documents (guidelines, manuals, policies) and then writes answers grounded in that content.

Healthcare use cases:

– EHR optimization based on internal architecture diagrams and vendor docs.

– Clinical decision support relying on local guidelines and formulary documents.

– Policy answers grounded in hospital SOPs rather than the public internet.

A nuance:

Mapping text diagnoses to ICD-10 codes can give almost identical results with or without RAG, because ICD-10 is a global, standardized, and very well-represented vocabulary in model training data.

In that case, RAG just adds cost and complexity (you must upload the entire code list) without a meaningful benefit.

Rule of thumb:

– Use RAG when your knowledge is local, proprietary, or fast-changing.

– Skip RAG when the task is based on mature, universal standards the model already knows (ICD-10, basic vital signs, common diagnoses)—but always validate outputs.

6. ReAct & PAL – getting the model to *do things*, not just talk

6.1 ReAct = Reasoning + Actions

ReAct combines chain-of-thought with tool calls: the model alternates between Thought → Action → Observation.

Example used:

1. Thought: “I need benchmarks for healthcare API reliability.”

2. Action: Search[API failure rate healthcare EHR]

3. Observation: The tool returns guidelines (e.g., acceptable failure < 2%).

4. Final answer: It compares that to the hospital’s 12% failure rate and flags it as critical.

In a production setting, “Actions” might be:

– Querying your observability stack (Grafana, Datadog)

– Performing a query in your database

– Hitting an internal API for uptime stats

– Looking up standards in your internal knowledge base

This pattern is powerful when analysts **don’t have direct access** to every system but can orchestrate tool calls via an LLM-enabled interface.

Available actions from a chat:

- File_search

- Msearch

- Mclick

- Python

- Web

- Gcal

- Gmail

- Gcontacts

- Image_gen

6.2 PAL (Program-Aided Language) – let code do the math

With PAL, the model doesn’t solve everything in text; instead, it generates a small program (usually written in Python), which is then executed.

Simple example:

> “If a hospital has 450 patients and 30% are discharged, how many remain? Write a Python program that calculates the answer. Do not explain, just output code.”

The model emits:

python

total_patients = 450

discharged = total_patients * 0.3

remaining = total_patients - discharged

print(int(remaining))

Now scale that idea up. In one of our internal examples, PAL was used to:

- Generate Python to process a 10,000-row timesheet table (people, roles, projects, hours).

- Run queries like, “How many hours did John Doe work on Project X two weeks ago?” without pushing all 10k rows into the LLM context.

PAL is a great fit for:

- Complex KPIs (throughput, length of stay, readmission stats).

- Time-series operations on large log tables.

- Anything where “LLM math” is too fragile.

7. Tree of Thoughts—exploring multiple solutions before choosing

For analysts and architects, Tree of Thoughts (ToT) is one of the most useful techniques. Rather than forcing a single reasoning path, ToT explicitly explores several candidate paths, evaluates them, and picks the best.

In the EHR performance context, possible “paths” might be:

- A: Infrastructure scaling (servers, caching, load balancing)

- B: API reliability (timeouts, retries, vendor SLAs)

- C: Data retrieval optimization (query tuning, indexing, pre-fetching)

A ToT-style prompt:

- Generate at least 3 different reasoning paths that could solve the problem.

- For each path, propose solutions and evaluate benefit, risk, and feasibility (we often score 0–5 or normalize to 0–1).

- Compare, then choose the best path or combination and justify it.

- Output the thoughts and final answer in a structured JSON/XML format.

We also experiment with different search strategies: breadth-first (investigate all possible 1st-level branches first), depth-first (investigate first branch till the end, then switch to the next one), or heuristic pruning with thresholds to stop exploring low-value branches early.

Use ToT for:

- IT roadmaps (e.g., “Upgrade vs refactor vs replace EHR components”)

- Vendor selection

- Complex trade-offs (performance vs cost vs risk vs clinician experience)

8. Protecting PHI & preventing prompt leaks

Healthcare means PHI, clinical pathways, proprietary protocols – all things you don’t want leaking out via prompts.

From a prompting perspective, we emphasize two practices:

- Use variables/placeholders in shared prompts

- Example: instead of pasting a real pathway, use

{{CLINICAL_PATHWAY}} or {{PATIENT_PROFILE}}in a generic prompt template. - At runtime, in a compliant environment, your system injects the real data.

- Example: instead of pasting a real pathway, use

- Use synthetic or anonymized examples when teaching

- Demo prompts based on “fake” patients and generic labs.

- Keep real PHI strictly in secure, audited systems.

We combine this with regular prompt reviews to avoid an accidental “prompt leak” where hidden instructions or secrets are surfaced back to the user.

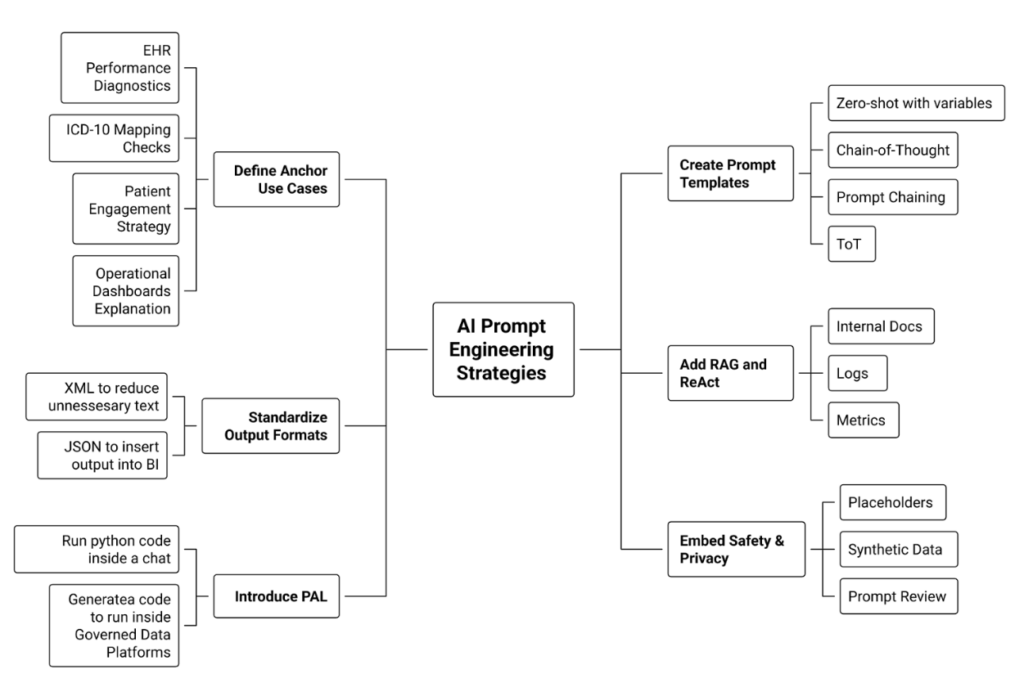

9. A mini playbook: bringing this into your hospital or health system

If you’re a CIO, CMIO, or analytics lead looking to operationalize these ideas, here’s a concrete starter plan:

- Define 3–5 “anchor” use cases

- EHR performance diagnostics

- ICD-10 / referral mapping checks

- Patient engagement strategy for a new app

- Operational dashboards explanation (“Explain these KPIs to a non-technical leader”).

- EHR performance diagnostics

- Create simple, reusable prompt templates

- One template each for Zero-shot, Chain-of-Thought, Prompt chaining, ToT.

- Standardize structure: Instruction / Context / Input / Output format.

- One template each for Zero-shot, Chain-of-Thought, Prompt chaining, ToT.

- Standardize output formats

- XML / JSON for issues, options, and recommendations so results can plug into BI tools.

- XML / JSON for issues, options, and recommendations so results can plug into BI tools.

- Add RAG and ReAct where data lives outside the prompt

- Wire in internal docs, logs, and metrics instead of copy-pasting.

- Wire in internal docs, logs, and metrics instead of copy-pasting.

- Introduce PAL for heavy analytics

- Use LLMs to generate code that runs on your governed data platforms.

- Use LLMs to generate code that runs on your governed data platforms.

- Embed safety & privacy from day one

- Use placeholders in shared prompts, synthetic data in training, and institute a “prompt review” habit.

What’s Next?

Prompting isn’t a magic trick—it’s a discipline. The Clinovera team’s experience shows that when analysts and PMs learn techniques like Chain-of-Thought, prompt chaining, RAG, ReAct, PAL, Tree of Thoughts, and structured outputs, LLMs become far more than chat toys: they turn into reliable copilots for healthcare IT and operations.